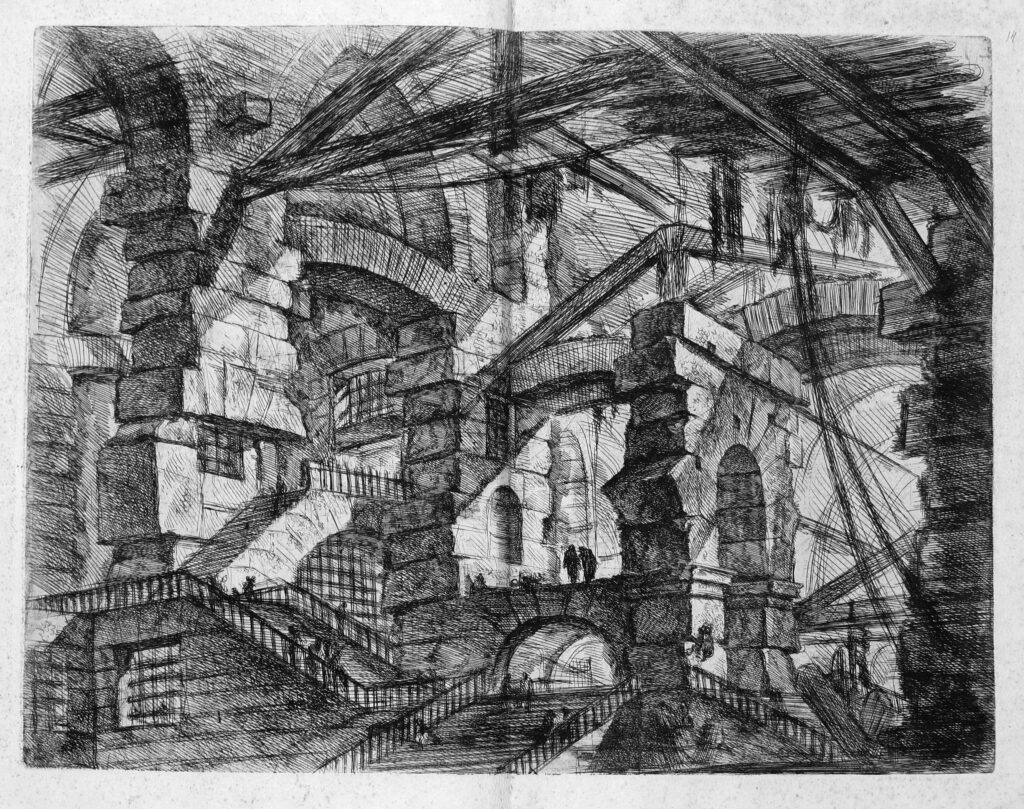

In José Luis Borges’ The Immortal, the opening story of The Aleph, the narrator, a Roman soldier, sets out to find the City of Immortals, an abandoned metropolis located across a desert – intrigued by the question: if its residents are truly immortal, where are they now? But instead of a splendid city, he wanders round a “labyrinthine palace” whose chaotic design seems intended to drive him mad. “In the palace that I imperfectly explored,” Borges writes, via Andrew Hurley’s translation, “the architecture had no purpose. There were corridors that led nowhere, unreachably high windows, grandly dramatic doors that opened onto monklike cells or empty shafts, incredible upside-down staircases with upside-down treads and balustrade. Other staircases, clinging airily to the side of a monumental wall, petered out after two or three landings, in the high gloom of the cupolas, arriving nowhere.”

Borges’ narrator is oppressed by the “dusty, humid crypts” of the city, which have a corrosive effect on his sanity, and even his memory. He eventually flees, terrified and disoriented, haunted by “the constant fear that when I emerged from the last labyrinth I would be surrounded once again by the abominable City of the Immortals”. The story explores our deeply ambiguous relationship with buildings and the adjectives we use to describe them: imposing, majestic, awe-inspiring and monumental. Rarely do we see a building described as comforting or benign. Rooms can be warm, generous and accommodating, but the structures that contain them are cold and detached – even though one of the most basic needs of civilised man is to have a roof over his head. Buildings are the most substantial expression of the human imagination, which is both a creative and destructive force, and Borges exploits our fear of being overpowered by them – the refuge becoming a prison. His narrator is revolted by the city that he crossed a desert to witness: “This City, I thought, is so horrific that its mere existence, the mere fact of its having endured – even in the middle of a secret desert – pollutes the past and the future and somehow compromises the stars. So long as this City endures, no one in the world can ever be happy or courageous.”

This gives rise to an intriguing question: can a building ever be happy? Buildings have lives: they are conceived on the drawing board, born in a frenzy of hard-hatted activity, acquire distinct characters as they take shape and enjoy decades (occasionally centuries) of vitality before (if they’re lucky) settling into a period of graceful decline. But in essence, they are built to serve us, and the rebellious slave is a recurring horror in civilised society. If our buildings are unhappy, how can we prevent them turning on us? And what will become of us when they do? The Immortal offers us an answer to this question – not an easy or comforting answer, but a powerful reminder that human creativity, for all its benefits, has a sinister and inescapable dark side.