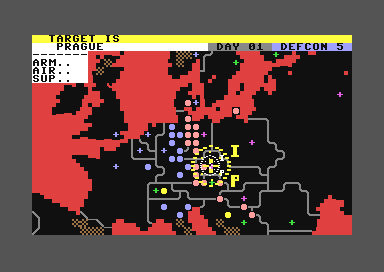

When I was growing up there was a computer game called Theatre Europe. It allowed you to play out, from the comfort of your Commodore 64 or ZX Spectrum, a 30-day campaign between Nato and the Warsaw Pact countries, and it had three possible outcomes: either one of the two sides surrendered or the entire population of Europe was wiped out in a nuclear holocaust. But what truly alarmed me, as a 10-year-old living under the perpetual threat of Armageddon in three minutes, was to read one of the game’s developers, Alan Steel, tell Zzap! 64 magazine that the strength of the two armies had been manipulated in the game, because when they ran a simulation with the real numbers, a Nato win was impossible.

Back then it was normal to assume that the world would end in a blaze of heat at any time in the next week to 20 years, and that the best way to delay this scenario was to pacify the bear. If the Soviet Union was ever stirred into sending its colossal army across Europe, we were done for. But the fact that you’re reading this should tell you that the Cold War didn’t end in a nuclear strike or even a skirmish on the Polish border. As the Dutch historian Geert Mak observed in his book, In Europe, the beginning of the end was on May 26, 1987, when a 19-year-old German, Mathias Rust, touched down in an unarmed Cessna plane on a bridge near Red Square in Moscow. How, we asked ourselves, could a teenage amateur aviator in a light aircraft fly unobserved into the heart of the biggest and most sophisticated military machine on earth? Until it dawned on us, gradually, that perhaps we weren’t looking at the most sophisticated military machine on earth at all. A year later the Geneva Accords were signed, cementing the USSR’s defeat in Afghanistan, and over the following three years the seemingly impregnable Iron Curtain crumbled. Soviet military might turned out to be a mirage.

Until a few weeks ago I was arguing that Vladimir Putin had no intention of invading Ukraine. Parking his tanks on the border was an elaborate bluff designed to scare Ukraine and the west into undertaking never to allow his neighbour to join Nato or the European Union. I wasn’t alone in this belief: I had recently read an interview with René Nyberg, the former Finnish ambassador to Moscow, whose country knows a thing or two about managing relations with Russia. Nyberg said Putin was operating from a weak position and could do no more than ‘act as a disruptive influence’ by bullying Ukraine into compliance. A full-on invasion would be unpopular and unfeasible.

Clearly recent events have shown this analysis to be wrong. But failure is instructive. Sam Greene has written candidly about how political scientists reasoned that an invasion was unlikely ‘based on the risks that a war entails for Putin domestically’. My own feeling, as a writer, was that the fiction of war was a far more powerful weapon for Putin than the reality. It made more sense to hold the permanent threat of invasion over Ukraine’s head than to send in the troops, an expensive and messy undertaking that was sure to have damaging repercussions. Russia, to use a cliché popular until three weeks ago, had nothing to gain from invading Ukraine.

Military strategists applied Occam’s razor and concluded that an invasion was the only plausible reason for amassing such a huge quantity of personnel and equipment on Ukraine’s borders. They were right. For me the penny didn’t drop until Putin delivered the snarling, paranoid speech announcing his ‘special military operation’ on February 23, in which he denied the existence of the Ukrainian nation and vowed to ‘show what real decommunization will mean for Ukraine.’ The fiction of war had been eclipsed in his mind by the savage mythology of ethnic cleansing.

As with many flawed analyses, the belief that Putin would stop at the Ukrainian border had solid foundations but poor construction. Russia indeed had nothing to gain from invading Ukraine and has spent the last two and a half weeks not gaining it with bells on. The calamitous battlefield campaign has diminished its military strength in both reputation and substance. The country is an economic pariah again. Nato has a new sense of purpose and the European Union has finally committed to weaning itself off Russian gas. All these developments will weaken Russia’s power and influence in the west. But this was a personal mission for Vladimir Putin, not just to subjugate Ukraine, but to reconstitute the totalitarian state where he went to school, and in that sense he has succeeded. Anti-war protesters are being slung into prison in their thousands. Foreign media has been banished and domestic outlets will be criminalised if they fail to employ state-sanctioned euphemisms, a move straight out of the Cold War playbook. Russia is disconnecting from the global internet, allowing Putin to impose Chinese-style censorship in the online sphere. With the Swift banking system blocked, China’s UnionPay is now a lifeline for Russians cut off from Visa and Mastercard. Putin may fail to bring Ukraine into Russia’s sphere of influence, but his actions have pulled Russia further into China’s sphere of influence.

Putin made the same miscalculation as the makers of Theatre Europe: he believed the numbers told the whole story. The invasion of Ukraine would be quick and decisive and offer only a light test of his forces. The west would grunt and puff and hit him with sanctions before sucking up the reality of a puppet regime in Kyiv. A new Cold War would begin, supported by a new fiction in which the large and mighty Russian army was poised to strike at any point on the European Union’s eastern border. But events in Ukraine have shown that the Russian army is not particularly mighty and becoming rapidly less large. By overplaying his hand, Putin has not only compromised himself in Ukraine, but made the worst possible start to the Second Cold War. The immediate cost will be terrible: lost lives in Ukraine, the ruthless suppression of dissent in Russia and the likely emergence of a new totalitarian alliance with China, with Russia as the junior partner. But there are many things we still don’t know, not least what personal price Putin will pay for believing his own fiction.